Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

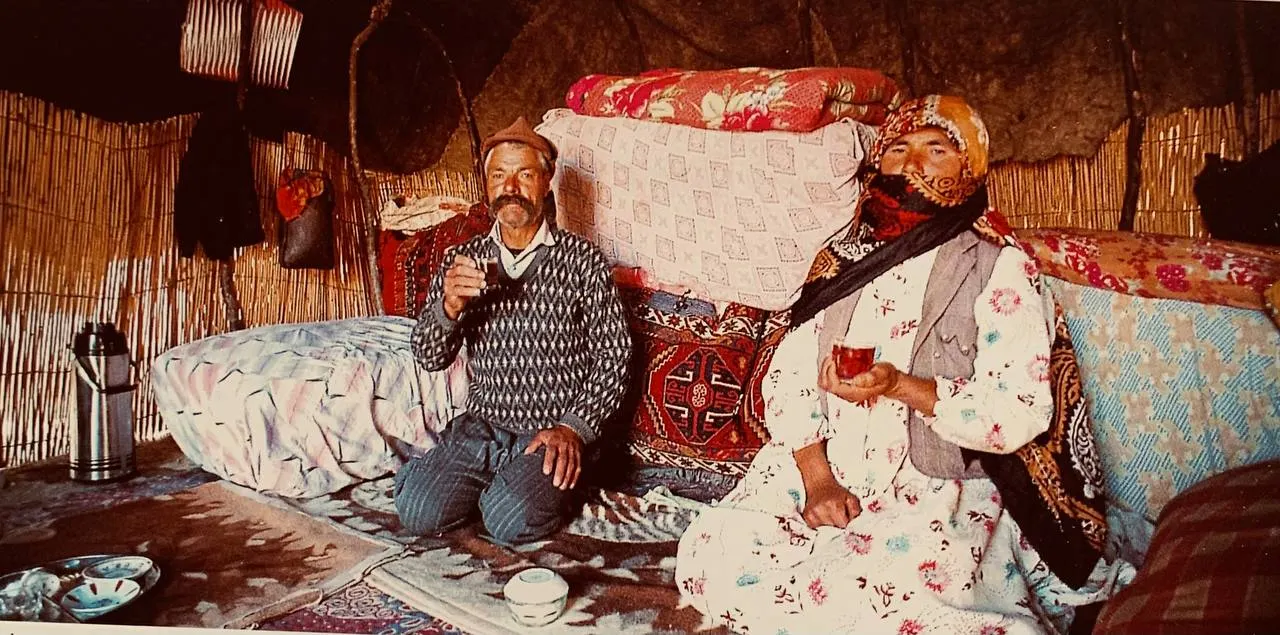

The Shahsavan Persian carpet , like all peoples of Turkish origin have a long weaving tradition. Still today, textile production is the domain of the womenfolk. Once their daily chores are complete, the women spend their free time at their looms. Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

Besides jajims, for which they are most noted, the women also produce carpets, kilims and bags. Each item is unique, not only for its design, but also for the skilful use of fine, lustrous wool.

Shahsavan weavings were ignored by merchants and scholars alike, until just a few decades ago. They have now established themselves in the collectors’ market, regaining their own identity that had been hitherto lost. Shahsavan carpets and kilims had been habitually classified in a number of ways. Sometimes they were confused with Caucasian weavings, sometimes with Kurdish and even with village weavings from Persian Azerbaijan.

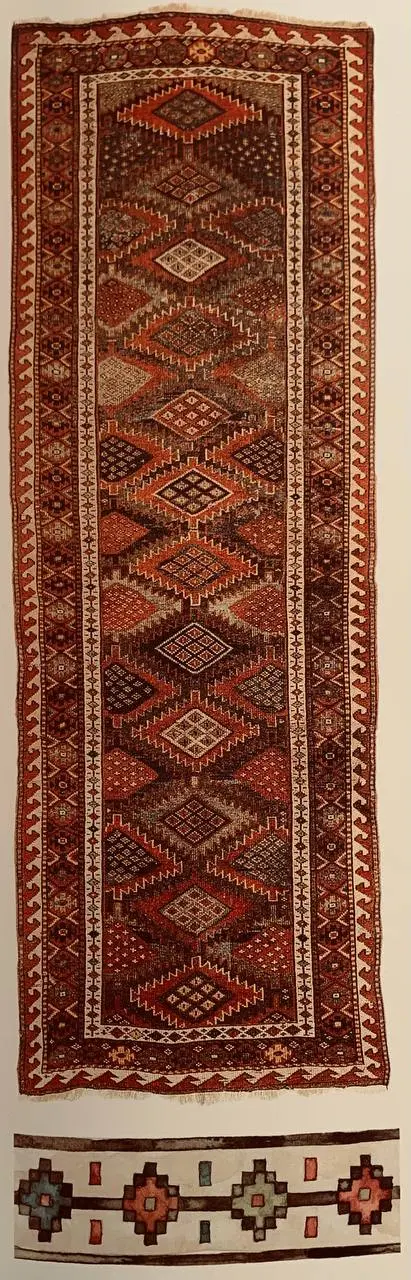

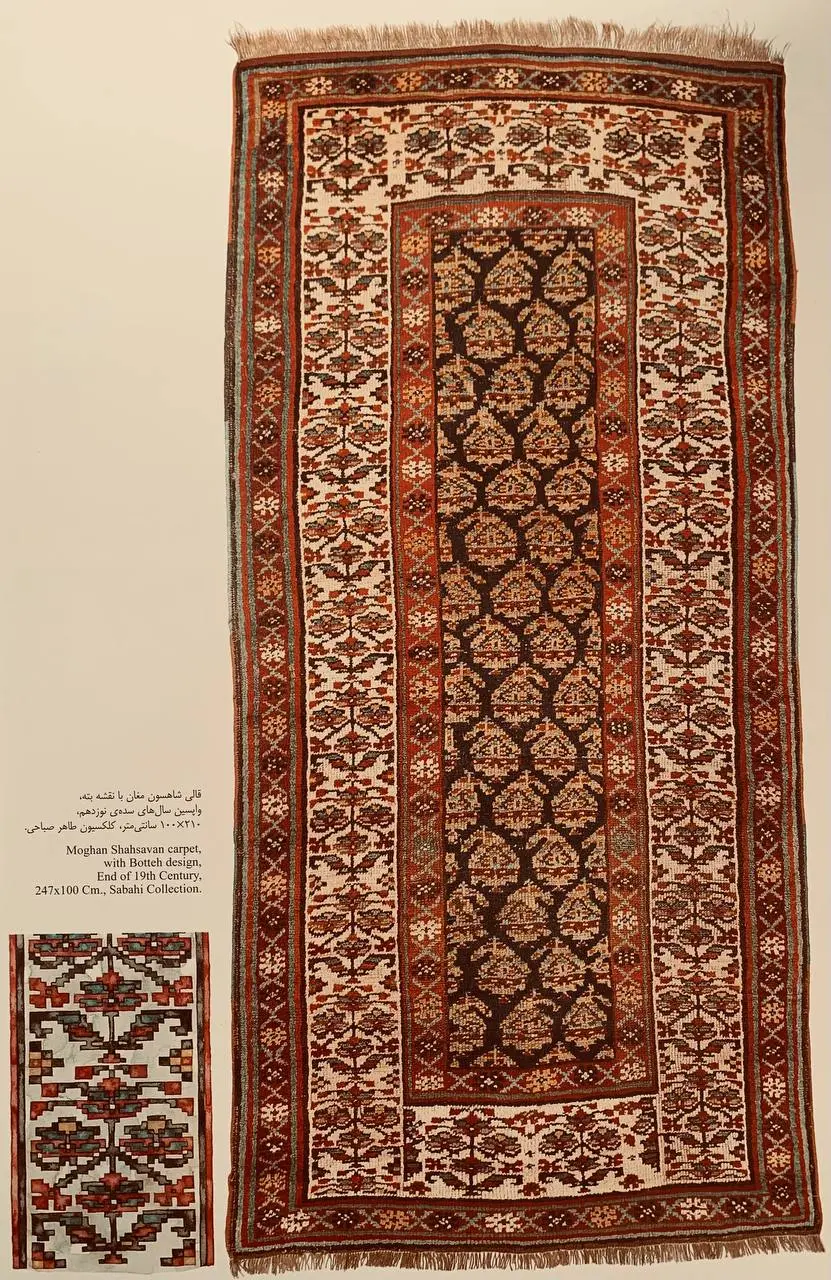

Carpets are the least noted of Shahsavan weavings, but have been the subject of meticulous study to accurately define their origins and to classify their decorative motifs. Many common motifs are also found in Caucasian carpets, especially those from Genje. Similarly, the same tones of ivory, red and green, much-loved by Genje weavers, are often found in nineteenth and early twentieth-Century Shahsavan carpets. Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

*Click on the opposite link to see precious Iranian handmade and machine combined silk carpets*

In more recent examples, the colours and designs are closer to Persian traditions, especially Kurdish. In fact, Shahsavan carpets are quite commonly classified as Kurdish and viceversa. The decorations, although heavily stylised, are inspired by plants and often arranged around a geometric medallion. persian Handmade carpet

The colours are becoming darker and are dominated by the classic juxtaposition of red and blue. Although detail and highlights in ivory are not lacking, the sheen on the carpets is almost silky. Vertical stripes are particularly loved. The design is characterised by the juxtaposition of clashing colours and the use of geometric designs, placed close together and arranged in columns down each stripe.

A very similar design is found on Shahsavan jajims. Without studying them in great detail, it is extremely difficult to attribute any of the various types of carpets to a specific clan. A study of their structure is not particularly helpful either, as they are markedly disparate.

This lack of uniformity in the techniques used to make carpets is a common characteristic of many nomadic tribes, and should not surprise. After all, the most common tribal

weavings are not carpets, but much simpler articles such as kilims and jajims. As luxury items, carpets are much more sensitive to changes of fashion in design and weaving technique. Innovative return to old carpets in Iran

Moreover, they are often made by those sections ofa tribe which have adopted a sedentary lifestyle. Living close to the rural population, they adopt local customs and this extends to weaving. Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

Although the traditional nomad loom is horizontal, it is not unusual to see Shahsavan women working indoors on rustic, vertical looms, especially in the winter months. Because of this, one finds Shahsavan carpets entirely made of wool with a double weft, loosely knotted with a symmetrical knot; carpets knotted on a cotton base, with just one weft and a symmetrical knot (similar to Kurdish weaving), and carpets on a cotton structure with a double weft and an asymmetrical knot, as is common in central Persia. Historical changes styles of Persian carpet

Kilims are woven in much greater numbers. They are essential items in the nomads’ homes and are quicker and cheaper to make, besides being extremely flexible. Unlike carpets, they do not have a pile but are made simply by weaving the warp and weft threads in a variety of techniques.

Shahsavan kilims are characterised by a technique known as slit-tapestry weave. These consist of a simple weave of warp and multicoloured weft threads. At each colour-change, the weft threads are turned back and wrapped around the last warp thread, thereby creating a slit which corresponds to the change of colour. For this simple reason, kilims produced in this way never contain designs which require vertical lines. Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

Diagonals are used instead or fragmented patterns, so as to avoid weakening the carpet’s structure with long slits. Ways of strengthening a slit-tapestry weave kilim exist, usually by warp-sharing. Alternatively, additional threads are added and used to sew up the slit. Many Shahsavan kilims are enriched with decorations made by additional weft threads.

These are added to the structural threads by a number of techniques, the most common being the so-called sumak. Here the weft are wrapped around the warps in a variety of ways to produce a strong, compact textile. Persian carpet designs

The most noted and indeed. impressive kilims are made on horizontal looms by the women

of the Moghan area. They can be up to five metres long and are made in two separate pieces, joined together by a strong central cord. The most common weaving technique here is slit-tapestry weave. Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

This is sometimes replaced by weft-faced plain weave in those kilims decorated simply with horizontal stripes. In most cases, Moghan kilims are decorated by series of lozenges, embellished with hook-like motifs and multicoloured threads on an ivory or blue ground. Along the top, the fringe is elaborately woven into complicated plaits and decorated by additional weft.

The Hashtrud Shahsavan produce less refined work than those of the Moghan. The threads used for the warp and wefts are coarser and made of poorer quality wool. The slits are more evident and the decorations are inevitably poorer and simplified. However, the use of colour, which

favours ivory grounds and soft, clear yellow, pink and green tones, lends their kilims charm and a certain value. Persian Rural carpet

The kilims from the Khamseh region are richly varied in design and colour. They are also of fine quality and beautifully made. The slits are often strengthened by extra-weft wrapping that outlines the patterns. This increases the weavers choice of design. Cotton is used extensively in both the structure and the design, to which white highlights are added. The weaver’s chosen motif is laid between wide, horizontal bands, decorated with embroidered hexagons or diamonds.

The kilims are enlivened with a free and easy use of colour, and through the contrasting use of dark blues and browns. Apart from this decorative scheme, which has strong tribal traditions, other influences are also present; for example kilims with motifs covering the whole field or medallions: both inspired by Kurdish kilims. Similar observations can be made of the kilims produced by clans around Gazvin and Saveh. Town carpets

Regarding the production of kilims by the Shahsavan of Varamin, it is well to mention the extent to which the nomads have settled and integrated with the other peoples. Today, it IS almost impossible to distinguish Shahsavan weaving from that of the lurs or afshar.

Weaving in the Varamin area has developed a style of its own, which combines elements from many different cultures. It still retains some characteristics of Shahsavan weaving, such as the insertion of decorative cord along the top of the kilim, or the use of decorated, horizontal bands. Kilims from this area are smaller in size than those described elsewhere and are made from one piece only.

The range of colours is dominated by darker tones than those used elsewhere. Among the most important and most characteristic objects from the Shahsavan looms are the so-called verneh: a

conventional term used to describe decorated items, produced in a wide variety of techniques. Verneh are produced in large quantities, and like kilims have been adapted for a wide range

of uses; from tablecloths to curtains, from blankets to saddlery.

Locally, they are often called gayek or zili as recorded by Latif Kerimov in his study.

These items are particularly common among the Shahsavan of Moghan whose verneh are often made from two separate pieces of cloth, stitched together along the centre. They consist of a balanced cloth base, entirely made from wool. Style and maktab of Persian carpet

The decorations can be few and placed well apart, or can be placed so closely together that the base cloth is almost completely covered. The decorations are made with weft-float brocade.

Where the motifs are small in size, the zili technique is used; where a larger area is to be covered, variations on traditional sumak techniques are used. Like base cloth, the motifs are entirely made of wool threads dyed in a wide range of subtle, yet rich tones.

The designs mostly consist of rows of repeated, geometric motifs, covering the entire field. Polygons, stars and diamonds often with stylised animals placed around them, are typical

motifs. The animals are usually four-legged and placed alongside peacockS and other birds with their tails fanned out. Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

Another characteristic Shahsavan motif is the stem crowned with a sunburst design, very often with a stylised version of a sun-eagle placed inside it. There is one kind of kilim, which distinguishes itself from other, similar weavings by its use as a tablecloth – the sofreh.

As Tanavoli observed, one can tread on a kilim, but it is highly offensive to walk on a sofreh. It is always carefully folded and kept in a bag and is only opened at mealtimes. Once open, the

dishes and food are laid out so that everyone may sit around it. Each family has a sofreh for everyday use and a finer one for festivals and celebrations. Every bride has one in her dowry.

The weaving technique used is identical to that of slit-tapestry weave kilims, with the weave often consolidated by extra-weft wrapping. Sofrehs are long and narrow in shape. The decorative

motifs are very sober, consisting of series of hexagons or stylised trees, which are confined to the sofrehs’ borders. Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

There is a second kind of sofreh, the sofreh ye nan, which is used in baking bread. These sofrehs are smaller and square in shape. Cross-shaped motifs cover the field and the borders are richly decorated. The women lay the portions of uncooked dough on them, and also keep baked loaves wrapped in them.

Among the Shahsavan, bread or nan is unleavened. The women work with water and salted flour, producing large quantities of dough. Once prepared, it is laid out on a flat stone and

made into thin loaves which are cooked in the fire, and wrapped in a damp sofreh.

The baked loaves keep for many days. Like other nomadic peoples, the Shahsavan produce a large number of sacks and containers, with an infinite variety of styles to correspond with their

many uses. The nomads have a name for each type. A chanteh is a small, square bag or satchel with a long strap. A tobreh is a kind of nose bag for feeding animals. Kooleh poshti and khorjin are the most common sacks and have many uses. Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

They are double-sacks, which are used as saddlebags, and in their smaller form, are worn across a person’s shoulders. Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

They are made by folding the two ends of the woven cloth towards its middie, leaving a wide band of plain cloth free between the folded areas. The two pockets thus created are secured with cords stitched around the sides.

The techniquce used for decorating a khorjin varies according to its component parts. The front of the pockets, or the ends of the strap are richly decorated using a variety of techniques, though they are seldom knotted in the carpet-making tradition. The back and the strip between the two pockets are usually made of plain or weft-faced weave, sometimes with multicoloured horizontal stripes.

One of the most popular decorative techniques used on the front of khorjins is the so-called sumak, or weft-wrapping used in different ways. Slit-tapestry weave is also found, though less used as it is not as hardwearing.

A double-row of specially-made wool loops run along the open edges of the sacks: plaited together, they close the opening. Alternatively, a more co complex method is used: rings are fed through a series of buttonholes and fastened together with a wooden stick which is passed through the rings. A series of straps and “buttonholes embellished with tassels are generally used as finishing touches. Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

Shahsavan khorjin are usually rather large as they are mostly used for keeping provisions and cooking utensils. Smaller examples do, however, exist. These are put to more personal use. Some khorjin are tiny and are threaded through belts and used as purses.

Khorjins are very simple objects and designed for everyday use. Their decorations are sophisticated, especially as they often contain iconographic themes, linked to the oldest symbols in the Turkish tradition.

Medallion motifs are the most common and are decorated with central motifs with ‘arms’ and hook- like motifs. Horizontal and vertical designs are also common,

as are checked pattens, which are often decorated with tiny geometric motifs. Symbolic figures such as birds and cagles, linked to the ancient cult of the sun, are also frequently found

on khorjins.

The sacks of most interest are the s0-called Namakdan. The smallest versions have a long neck and two handles on the sides. Their primary use is to contain salt but they are also used for other loose food items such as rice, flour or sugar. The long neck on the sack serves to make it easier to empty.

The handles make them easier to move and at the same time are useful for hanging the sack on the tripod, or from the frame of the alachiq. The way they are made and the decorations used. are very similar to those described for khorjin. However, one should mention the particular care and attention paid to the stitching and to the lower part. This is often reinforced with pieces of leather, or alternatively stiffened with a series of rich, sumak decorations.

The Qäshoqdân are equally interesting. They are used for keeping spoons and kitchen ladles and are highly decorative. Usually, they consist of three square pockets, similar to a chanteh. The middle pocket is the largest, the other two being much smaller. Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

The pockets are sewn together and hung from a richly decorated band. A heavy net, made by weaving thin strips of material together, and decorated with a row of tassels sewn along the bottom, add the finishing touches.

The band allows the Qâshoqdân to be hung from the frame of the Alachiq during stops and from the camel’s pack saddle while travelling. Among the most noted and interesting of Shahsavan

weavings are the large Mafrash or Farmash: capacious trunks with six sides, (parallelepiped) and more than a metre in length.

Its base is approximately twice its height. The nomads use them for storing clothing. bulky household items and above all, bed- rolls. They are made of one long strip of cloth forming the base, two long sides, which sometimes have a closing fiap along the top and two square-shaped shorter sides. The latter are woven separately.

The component pieces are sewn together with strong stitching, which is is usually protected by coloured, woollen cords. A system of buckles and leather straps, or alternatively, “buttonholes’ and cords provide an effective fastening.

Strong wool rings in the corners and along the top make the mafrash easy to lift and transport.

Traditionally, the principle material used to make Mafrash is wool, though cotton is sometimes used. Occasionally, silk or metal threads are used to give the effect of light to the decorations.

A wide range of flat-weave techniques are used to make them. The most common are slit-tapestry weave, which is accompanied by various methods of consolidation, and sumak It is less common to find a Mafrash with the front sections knotted, as in a carpet.

Mafrash are considered status symbols within the tribe, as a family’s wealth is measured by the number and quality of the Mafrash it takes on migrations. Similarly, the beauty and quantity of the Mafrash in a young girl’s dowry are an excellent means of introduction to prospective suitors. Usually, they are made in pairs so that they can be hung on both sides of a pack

animal.

A dowry would normally consist of at least one pair. Given its social importance, one should not be surprised then, to see mafrash embellished with extraordinary finesse and quality.

The decorations are often organised horizontally, with the central decoration being the largest and most important. Less important decorations can be found on the sides. Weaving traditions of the Shahsavan

The decorations are usually placed inside panels and enclosed by borders. Here, the customary decorations consist of a series of losenge-shaped medallions, which are often embellished with hook-like motifs. It is common to add other, less customary decorations; for example, checked patterns, embellished with small medallions, or decorated squares with multicoloured inscriptions, Memling gul and many others.

The result is a varied and rich repertoire of designs. These traditional crafts are without doubt evocative for their colours, designs and the finesse with which they are made. Besides the items described here, and among the most interesting of all Shahsavan weaving, are jajims.

These are simple pieces which may seem poor for the sobriety of their decorations and their basic structure. However, they are a better witness than any other to the textile tradition of the Shahsavan people.