Introduction The Shahsavan Jajims

the fascination which the distant lands of the Orient have held in the West, has always been associated with the valuable merchandise that has reached its shores. Persian carpet Goods that had travelled along dangerous caravan routes to the merchant ships, which then carried them to the Mediterranean ports. The Shahsavan Jajims

Among these precious commodities were spices and herbs, silk and other textiles; from warm, sumptuous carpets to fine cloth. The Shahsavan Jajims

The skills of the Eastern weaver first became famous in the West during the Crusades, when relics of the saints began to arrive from the Holy Land, wrapped in precious cloth. Many of these wrappings can still be seen in cathedrals today. The West learned to appreciate the sheen of the wools and silks, the vibrant colours and the discipline and elegance of the geometric designs. All these elements are to be found in Jajim traditional weavings, which were already commonplace in the East in medieval times. The Shahsavan Jajims

*Click on the opposite link to see precious Iranian handmade and machine combined silk carpets*

They were not made with any ceremonial purpose in mind, but for everyday use. From the fourteenth Century onwards, miniature paintings of resting sovereigns, heroes and warriors

show Jajims in use, either lying open on the ground or being used as blankets. There is a long tradition of using warm wool or silk for bedding. The miniatures show the cloth as being

decorated with thin, multicoloured stripes and dotted with motifs, which are believed to bring good luck. persian Handmade carpet

This weaving tradition continues to this day and has, among its protagonists, members of one of the most feared confederations of oriental nomads: the Shahsavan, or rather “the faithful of the Shah.

Descendants of proud Turkic peoples, who at various moments in history have reached the Iranian plateau, the Shahsavan are first mentioned as supporters of the then Shah in the sixteenth Century, when the Safavid dynasty established itself. Silk carpet

In the following centuries of peace and splendour, the Shahsavan were one of the most powerful peoples in western Persia. Today, they are reduced to a handful of tribes who, since the advent of the Russian border, have been deprived of the most fertile pastures of the Moghan. Innovative return to old carpets in Iran

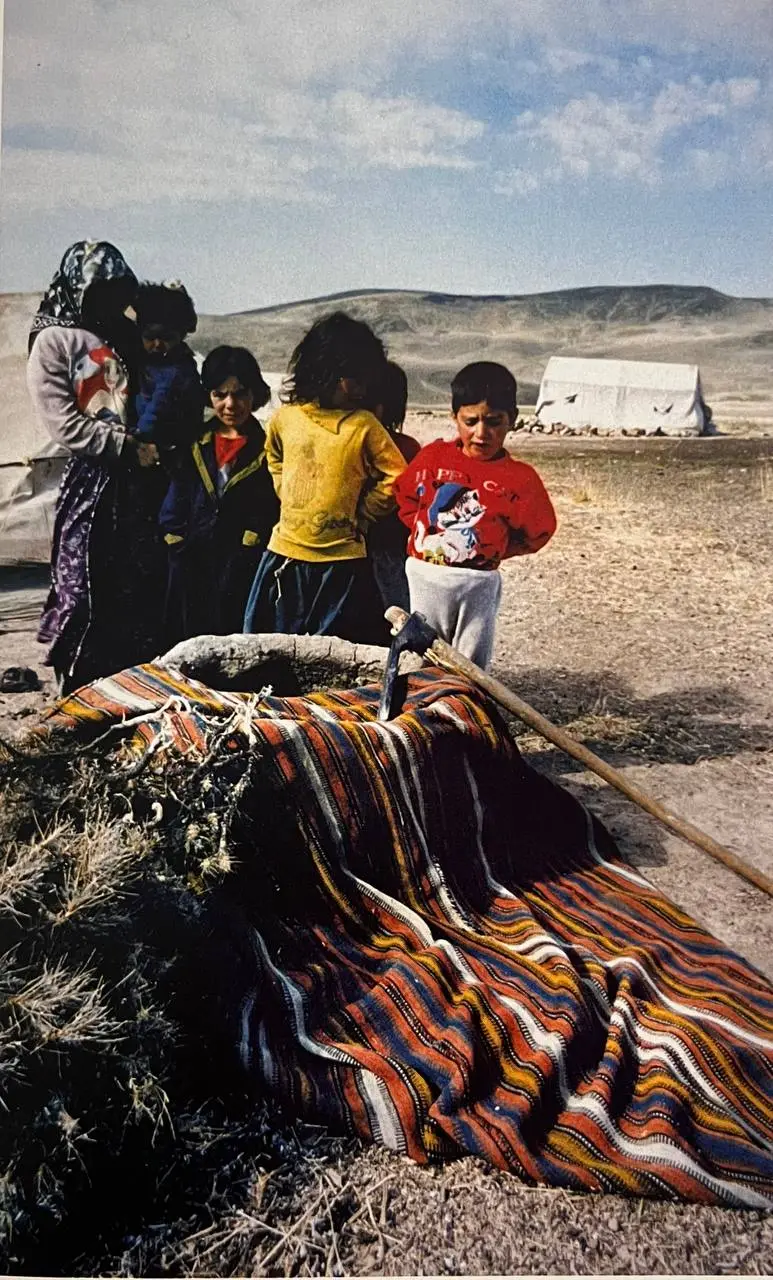

In spite of this, the Shahsavan continue to live their traditional, nomadic life, migrating from their winter quarters on the plains to their high, summer pastures. The Shahsavan Jajims

Their ‘mobile homes are made of light poplar wood and covered with white felt. On the inside, multicoloured jajims make the ground comfortable and cover the many sacks and bedrolls as they have done for centuries. Historical changes styles of Persian carpet

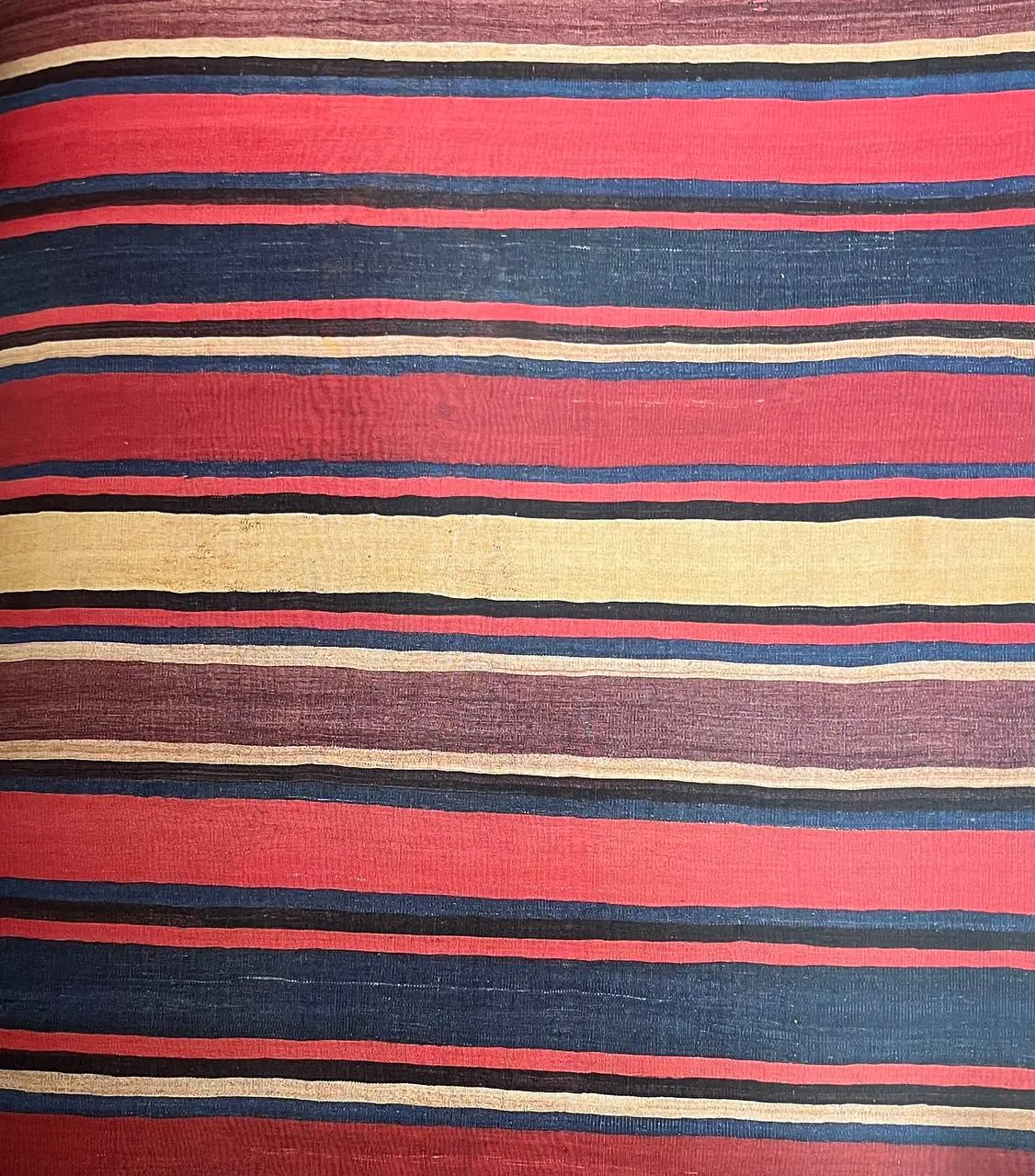

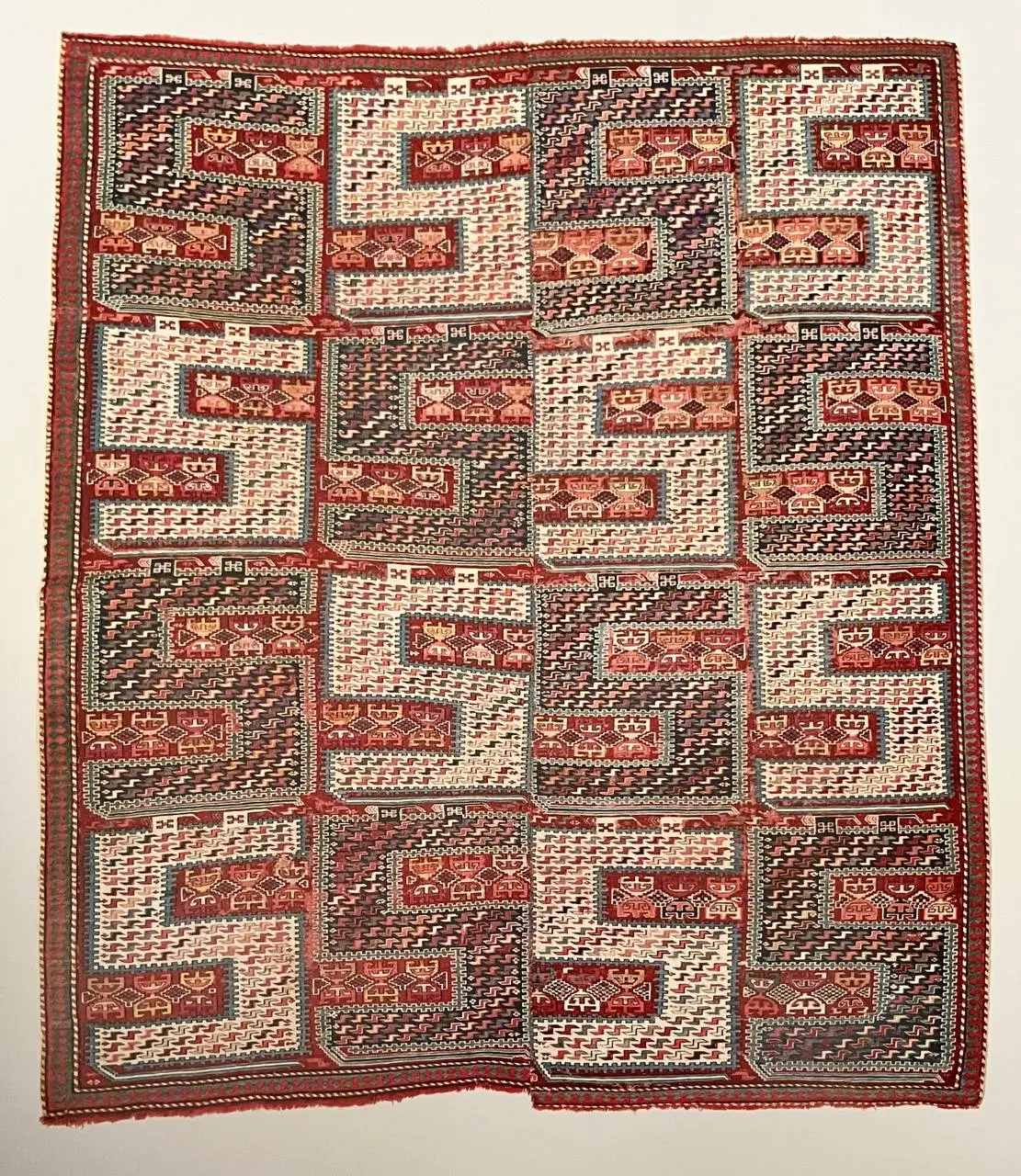

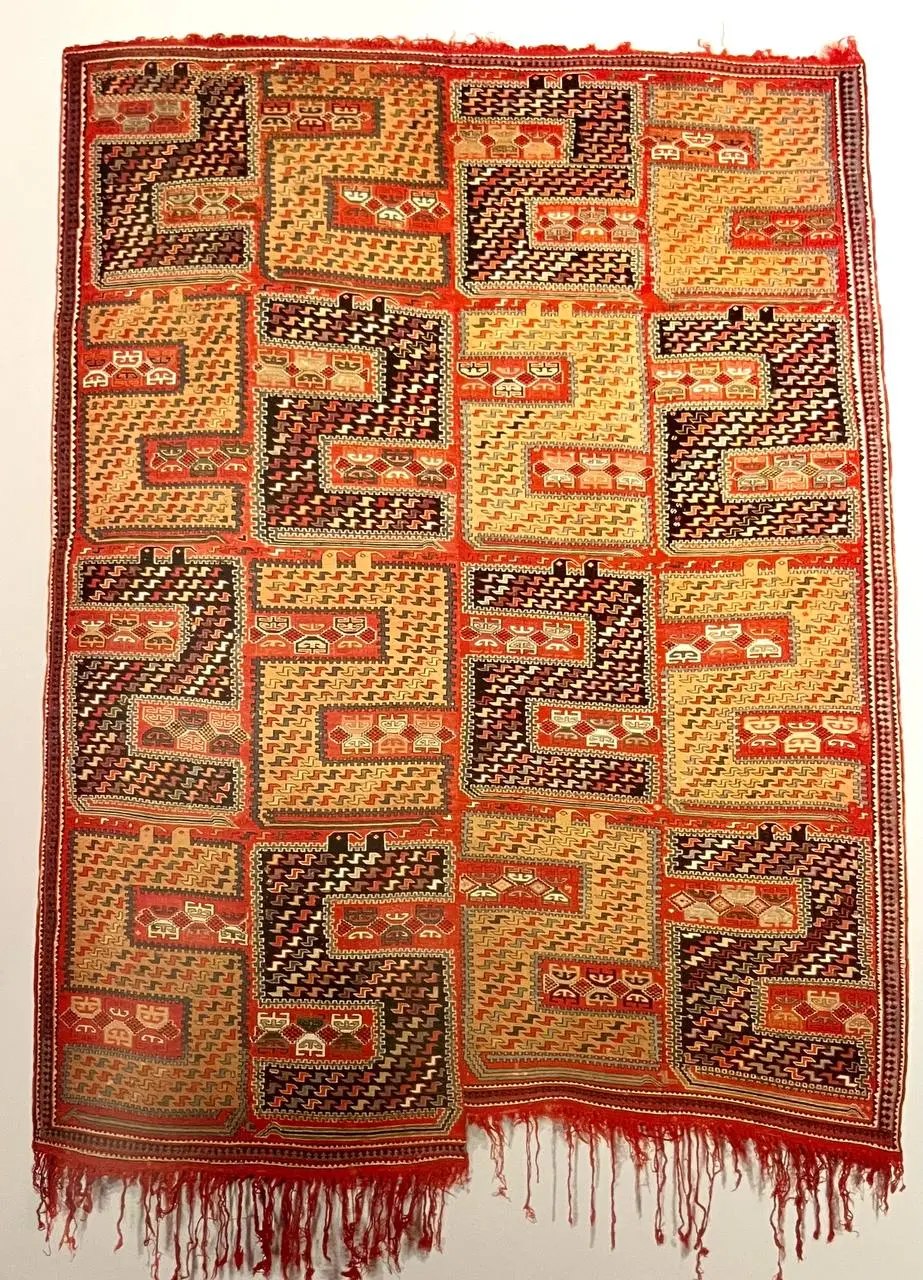

Every young woman has several jajims in her dowry. Made on simple hand looms, jajims are made of long strips of cloth sewn together. They still maintain the traditional pattern of thin, multicoloured, vertical stripes. The women weave in motifs taken from an age-old tradition. Each is a good-luck charm with its own hidden meaning to ensure safe, peaceful rest to whoever wraps the jajim around himself. The Shahsavan Jajims

A multitude of coloured warp threads pass from the front to the back of the jajim to produce sinuous motifs reminiscent of the huge, fearsome dragons ofAzerbaijan tradition and stylised,

geometrical eagles with outstretched wings, sharp claws and hooked beaks. Many are woven with the designs of amulets and talismans as worn by Shahsavan women on their foreheads and on the front of their dresses, and others with the flowering tendrils so common in oriental textiles. Persian carpet designs

Largely ignored in the West, (as once were kilims) jajimsرwere believed to be of little importance, and were neglected in favour of carpets until a few years ago. Today, jajims are

finally coming to the attention of collectors. In the last few years, many have recognised their extraordinary and essential beauty. Scholars have learned to recognise, in the jajims’

simple geometry, motifs and symbols common to the oldest decorative traditions of the Iranian plateau peoples. Persian Rural carpet

Merchants have begun to appreciate their exceptional technical qualities, the weavers’ skills and the first-class materials used. Among the most important are silky Azerbaijan wools and silks, which are dyed in the characteristic, natural reds. The Shahsavan Jajims

The Shahsavan Jajims

Tajim weaving is carried out in tandem with the production of carpets and kilims in most oriental countries. The term jajim and the group of words similar in sound and origin to it, are used to describe a large group of weavings. Style and maktab of Persian carpet

The word jajim is often used as a term for cloths which are used as covers, or for protection. It is more correctly applied to those textiles which are decorated with thin, multicoloured, vertical stripes. The Shahsavan Jajims

These may be devoid of any type of decoration, or alternatively decorated with tiny motifs, placed one behind the other, in a strictly observed sequence. Apart from these, the term jajim

often refers to simple textiles which can be used to make shawls, turbans or clothes, in accordance with ancient oriental custom.

Due to their delicate structure, the oldest examples of jajims in museums or private collections rarely date back further than the nineteenth Century. However, historical and more importantly, pictorial sources bear witness to a much older tradition. Pazyryk carpet

In Persia, ‘the art of the book’ has ancient roots and there are many examples of miniatures showing thinly-striped cloth in use. Close examination shows them to be the forerunners of the modern jajim. Paintings usually show them as being used for bedding; as indeed they are today.

It is still customary to use a jajim as a bedspread or as a blanket, though they are often used as a cushion or as clothing, and sometimes as a saddle cover. One of the oldest references to them can be found in Jami al-Tawarick (The History of the World ) by Rashid al Din. The Shahsavan Jajims

It was written in Tabriz in 1314, under the auspices of the Ilkhanid ruler Uljiaytu, and was once owned by the Royal Asiatic Society. The book is illustrated with illuminated letters and miniatures, one of which (sheet 3r) shows the surrender of a Jewish tribe to the Islamic army.

The clothing worn by the characters is painted in great detail. One of the victorious soldiers is wearing a long tunic, drawn at the waist, with alternating red and white strips dotted with tiny decorations. It is similar to a type found in the countries of Central Asia today. The Shahsavan Jajims

A more traditional use of a jajim is shown in another antique miniature. Firdowsi’s Shahnama was made between 1335 and 1336 and can be seen in the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, in Washington de. It shows the coronation of Zal. Origins of Persian carpet

Here, he is already crowned and seated on his throne and about to receive gifts and homage. His throne is covered with a specially-shaped cloth with rounded edges. It is decorated with stripes in a wide range of tones: from white, black and red to brown, as indeed are the most common jajims.

Among the most famous and quoted illustrations to bear witness to the ancient tradition of the jajim, is an edition of the Khalila wa Dimna. Attributed to Tabriz in the second half of the fourteenth Century, it is a lively depiction of a thief, who is taken by surprise and captured whilst in a lady’s bedchamber.

The lady, awoken by the intrusion into her chamber, modestly holds a blanket tightly round her legs. The painter, contrary to the custom of the period, has shown her startled movements by painting folds in the cloth. It is perhaps made of soft wool or silk and has a red ground with alternating stripes of gold and blue with broader, white stripes, edged by a row of V-shaped

‘teeth’. It is very similar to a type still in use today. The Shahsavan Jajims

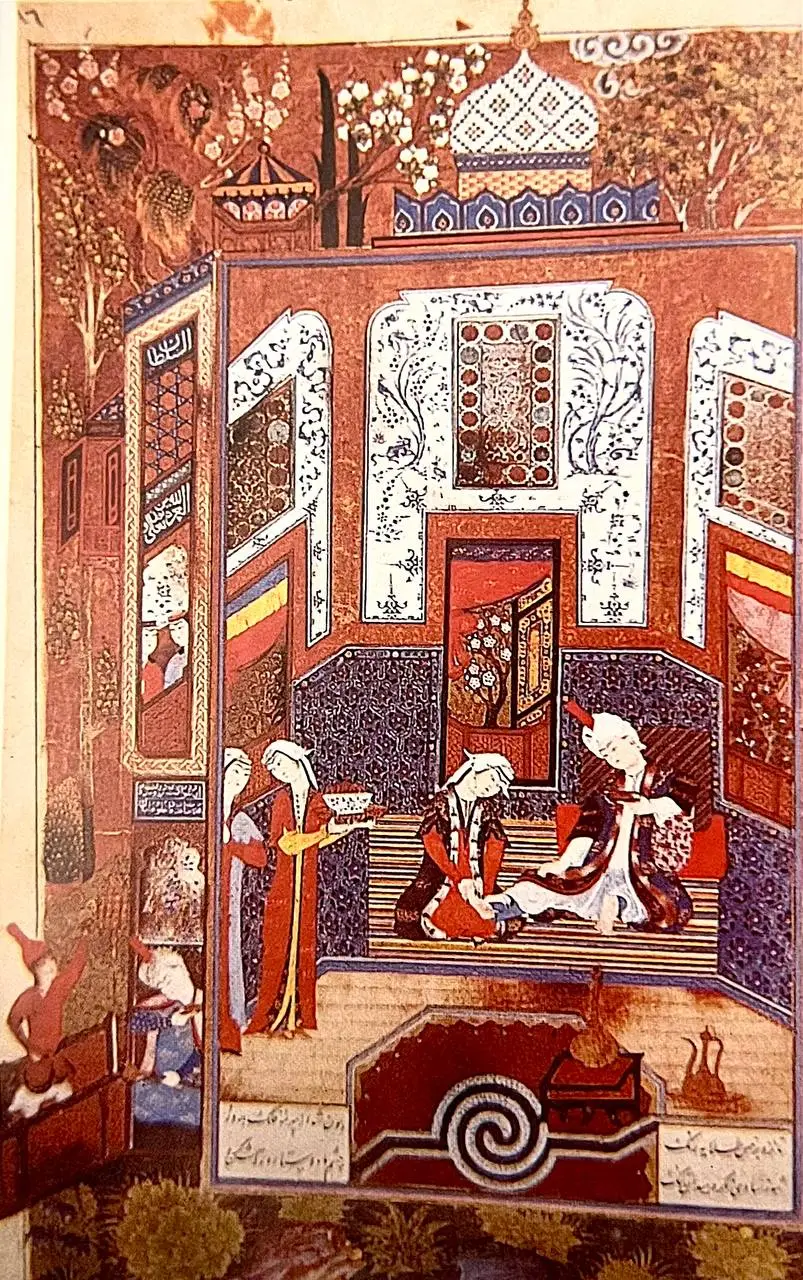

In a slightly later miniature which accompanies a copy of the poem Khosraw and Shirin, one can see a firm jajim cushion supporting Shirin’s back. She is surrounded by her handmaids as she receives Farhad. Persian carpet

The cushion has thin, red and black stripes on a white ground. Some speckling suggests a series

of small motifs. (The miniature, which was made in Tabriz between 1405 and 1410, can be seen at the Freer Gallery in Washington de).

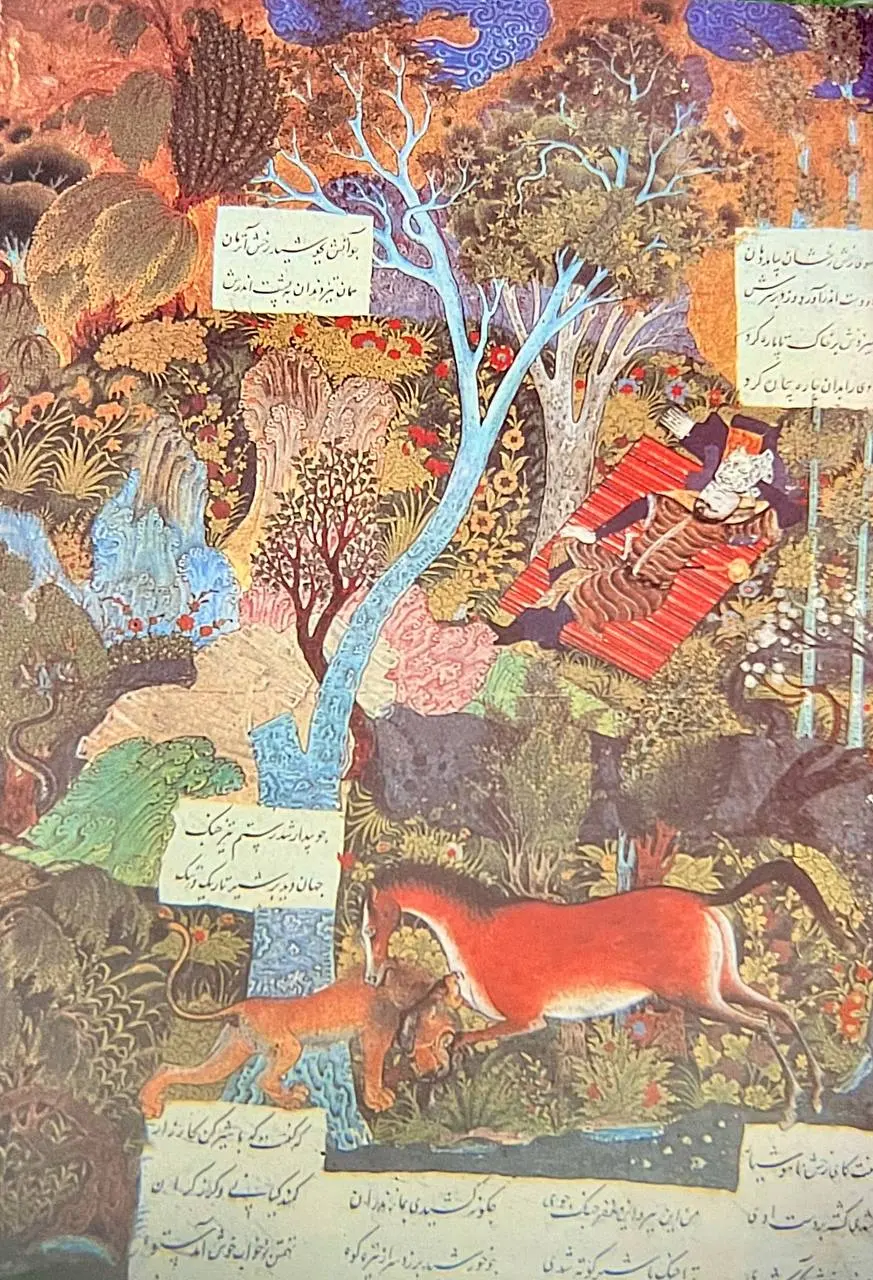

In a love-scene from Gulistan, by Sa’di, much richer decorations enliven the cushions and cloth which have been thrown onto a large carpet, and form the background to the scene. Painted in Herat in 1426 (Chester Beatty Library, Dublino), it shows a young woman, almost buried in the mass of cushions and carpets, trying to escape the advances of a prince, with the helped by his servants.

The scene is lively and the room is painted in great detail, showing the use of a large jajim as a cover for a sizable, valuable carpet. The jajim has red and brown stripes, which are devoid of any motifs, alternating with other stripes in black. The couple are reclining on a backrest of two cylindrical cushions placed side by side.

These are also covered in a striped cloth. The cushion on the left-hand side is ídentical to the cloth covering the carpet. The other has a light-coloured field and is decorated with a ‘tooth’ pattern. Both are edged with trimmings and a fabric edge which repeats the main striped pattern, but is placed at different angles.A simple jajim is again used to cover the inside of a throne (identified as such by its tall, rich, wooden structure) in an illustration from a Shahnama by Firdowsi.

The picture is attributed to the Herat school and is dated 1429-1430. In this instance, the throne belongs to the sovereign Lohrasp, and the picture illustrates some dignitaries telling him of Khosraw’s disappearance. The jajim, which is blue in colour, covers the back of the throne and

is folded several times under the cushion. That a very ordinary weaving should be a status symbol leads one to think that fine examples of jajims in silk, similar to those found today in the

Caucasus, were in use at that time.

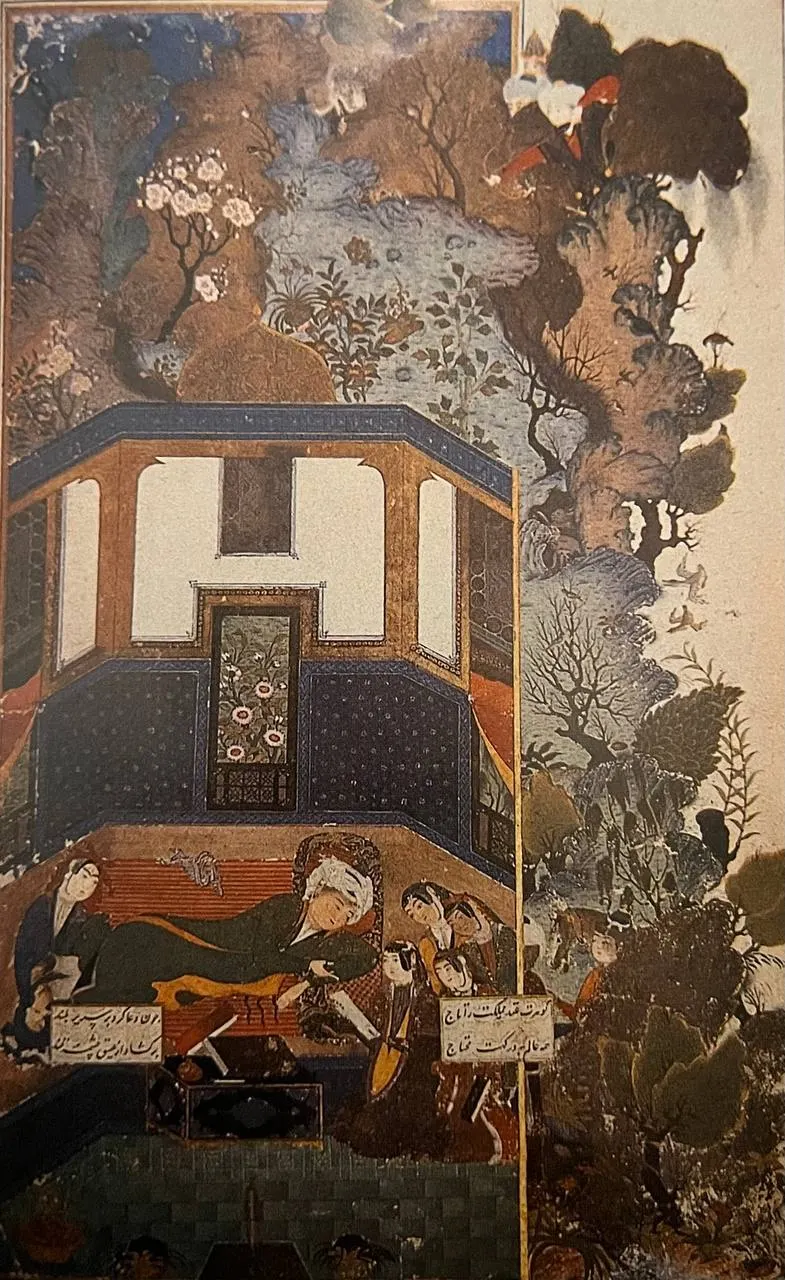

A copy of the Shahnama of Firdowsi (British Library, London), which was made several decades later and also attributed to Herat, contains an illustration showing a much more unusual use for a striped cloth. This time, the scene is not in a palace, but in the depths of a forest.

The hero Rustam is resting and has fallen asleep, having spread a scarlet cloth with thin, black stripes, on the ground. (Perhaps it is a caparison, and he is using the saddle part as a pillow). While he sleeps, his heroic steed Rakhsh kills a lion, which was attempting to stalk Rustam while he slept.

The princesses in the Khamseh of Nezami show little originality. They are receiving the hero Bahram Gur in their variously coloured pavilions. Each of them offers Bahram Gur a bedroll, covered in a fine jajim. In the famous copy of the Khamseh made in Tabriz between 1475 and 1481 (Topkapi Saray Muzesi, Istanbul), the princess of the Yellow Pavilion opens a large jajim for him.

The cloth is green with stripes dotted with a sequence of pearl-like motifs, alternated with

wider stripes with a sinuous weave of S-shapes. It appears to be edged by a gold-coloured stripe.

The princess in the Green Pavilion has prepared a red and black cloth, which is covered in narrow stripes. It has been made more comfortable by the addition of a large, cylindrical

cushion with a dragon design on it.

The princess in the White Pavilion, who figures in a slightly later version of the poem, offers Bahram Gur a jajim-covered cushion and a carefully-spread cloth with thin, multicoloured

stripes.

Other uses of the jajim are documented in slightly later miniatures. In a version of the Khamseh of Herat dated 1485. a person witnessing the death of Sheikh Iraki wears a dotted. red and white jajim shawl.

In two different illustrations from a later still copy of the Khamseh made in Shiraz between 1507 and 1508 (Saltykov- Shchedrin Public Library of St Petersburg), show Bahram and Sultan Sanjar out riding. Under each war-horse’s saddle is a large, fan-shaped caparison made from a jajim. The cloth can be identified by its multicoloured series of stripes, varying from ivory to yellow and red.

They are decorated with tiny motifs, tendrils and a tooth-like pattern. These illustrations

document the ancient origins of this type of horse-cover, which is still widely used in Turkmenistan today.

The priceless Khamseh of Sharukhiya, made between 1521 and 1522 (St Petersburg Library), shows small jajims carefully edged with wide borders, each with different decorations executed in dark colours. The jajims are spread on the ground in front of some extremely elegant carpets.

Here they are being used as tablecloths: chalices, plates and long-necked bottles having been placed upon them.

A richly-decorated jajim features in a miniature from the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp. It was made in Tabriz between 1527 and 1528, and has been attributed to Mir Musavvir. The jajim has

a flowery decoration, reminiscent of boteh, placed in sequence within wide borders. Upon the jajim are the lovers Ardashir and his young slave Gulnar.

The work is considered one of the most romantic miniatures of the classical era. Later illustrations. attributed to the Qajar period, docunment the widespread use of striped cloth, presumably jajim, not only as covers, but also as shawls and clothing. These document the continuity of the production of these simple objects, which among the nomadic peoples, have a large number of roles and uses.

Jajim weaving is common to a number of geographical areas. In Turkmenistan, nomads weave large cloths and fine jajim, which are used to make shaped horse-blankets or at-joli. These are sometimes made with silk thread. In the Bakhtiari tribe, jajims formed the basis of their traditional dress and were used in an wide variety of ways inside their homes.

They are also common among the Qashqa’i as among the Afshari. Yet, both enthusiasts and collectors often automatically associate jajims with the Shahsavan. They are, after all, among the most important producers and dedicate particular care and attention to their weaving. Their jajims are extremely fine and embellished with much sought-after decorations.

In Azerbaijan, silk jajims have been attributed to the Shahsavan, and were mentioned in a number of Russian sources during the late nineteenth Century and the early twentieth.

For those Shahsavan who have not yet completely abandoned the nomadic way of life, jajims are everyday items, which are able to combine total adaptability with an undisputed decorative value. Their aesthetic qualities are highlighted by the weavers’ free and lively use of colour.

From the jajim’s most common use, that of a simple floor- covering in rural houses or tents, there are many permutations, such as using them to protect valuable carpets from dust and unnecessary wear. They are often used at mealtimes as tablecloths. They can be used to cover benches and trunks; the main items of furniture in the Azebaijan house. In the winter

months, they are used to cover the korsi, a low table which stands over the brazier.

A jajim large enough to touch the floor on all sides, is thrown over the brazier, so as to contain the heat. Everyone then sits around it with their legs under the jajim to keep warm. Multicoloured jajim are also used to cover large bolsters, or balisht, or shaped cushions. These often take the place of sofas in the oriental home and offer back support when resting.

At the hammam, a large jajim will often become a bath towel. It can also be used to wrap a change of clothes and toiletries, or to cover a bench or flooring. Thanks to its versatility, the jajim is often the textile used to make sacks and containers of various types and sizes, from small khorjin upwards.

These are made of a long strip of cloth folded back on itself at both ends to make two pockets. Cords are then added for the fastening. Sometimes boghcheh, an envelope-like bag used by Oriental women to hold their personal effects, are made from jajims. Again, tape and cord are added for the fastening.

It is not unusual, not even among the Shahsavan, to see saddle-cloths made in the jajim technique. Sometimes they are simple cloths with a leather strap to adapt them to their new role. In other cases, two side-pieces are added to the front so that it can be tied across the horse’s chest.

To make the cloth stronger, given their limited resistance to wear, it can be lined with felt. This is fixed in place by stitches along the edges and along the stripes of the jajim, to keep the two fabrics together.

Thus, a new kind of cloth is created: colourful, strong, warm and particularly adapted to

the sometimes inclement climate of north-west Iran. Apart from the warm, wool jajims, the Shahsavan have, for many centuries, made jajims in silk.

In western Azerbaijan, south of Ardebil is a large agricultural area around the town of Khalkhal, where mulberry trees are grown and silk worms raised. Of the villages in the area, Nimhel is the most important for silk jajim weaving.

There are about 180 families there and most of them are settled nomads. Silk jajims are

also woven in Barandaq and Monamin. Like Nimhel, these two villages are situated on the banks of the Qezel Owgan. The silk is produced in the traditional manner by the women

of the villages and is used for the warps.