Weaving the Jajim

Tajims are objects made for everyday use, though thanks to the nomads’ ancient Persian carpet weaving tradition, they have become rich in technical and decorative detail. Because they are commonplace objects made for everyday use, the tools used to make them are extremely simple, and with few exceptions are readily available. Weaving the Jajim

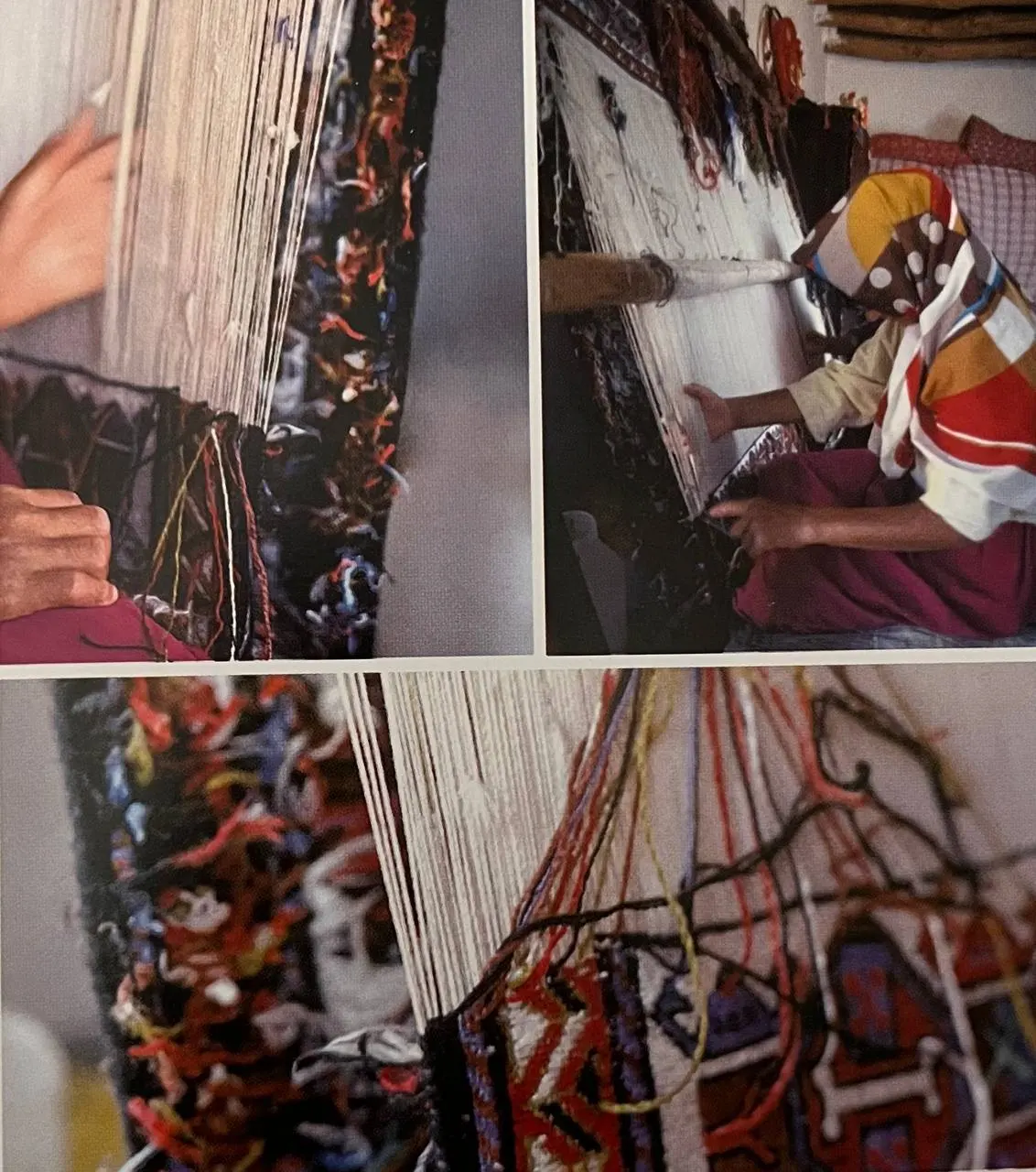

In recent times, those Shahsavan women who have settled in villages, have started weaving their jajims on the same rustic, vertical looms used for weaving carpets. However, the traditional nomad loom and that used for weaving jajims, is horizontal.

*Click on the opposite link to see precious Iranian handmade and machine combined silk carpets*

The loom is very simple and easily moved. It is usually placed on the ground, next to the alachiq and can be opened out to a length of several metres. It consists of two parallel, cylindrical beams placed at the desired distance apart, which is defined by the length of cloth to be woven. They are then fixed in place by crossed pegs.

The warp is stretched between the two beams, or jutamda, in sections of different colours. Sometimes, the front beam is replaced by a smaller bar. persian Handmade carpet The warp threads are run around this before being grouped together in a bunch and firmly held in place by an end-peg: the kapeyna pura, which keeps the warps in tension. A low, portalble tripod, whose legs are driven into the ground, supports the heddle.

This separates the warp threads from each other so that the weft threads can be passed between them. After each time the weft is passed through the warp threads, it is beaten down with a weighted comb, which is inserted between the warp threads nearest to the weaver. The

comb’s handle is often carved at the ends.

The women sit huddled over the loom on a low bench, placed across the stretched warp threads. With this simple structure, if well-constructed, it is possible to weave strips up to ten metres

in length. The width of the cloth rarely exceeds 50 cm. Several pieces are then sewn together to make a jajim. Its small size makes the loom more manageable and the use of longer and

stronger beams unnecessary. Silk carpet

These would inevitably be more difficult to pack and transport. Instead, the lightness of the loom means that it can be easily moved at any moment. When it is time to move, the warp threads are rolled up in the already finished cloth, along with the heddles and the beams. They can

be easily re-tensioned once the new encampment is reached.

The warp threads, as already mentioned, are grouped in bands of different colours. This is essential to the weaving technique used for the decorations on a jajim. The warps are usually made of a fine, though very strong wool. The wool is chosen and prepared for weaving with great care.

In order to maintain the correct tension, regardless of length, the threads must be consistent in elasticity. These are fortunately, characteristics of spun wool. Fine, long-fibred wool from the shoulders and stomach of the sheep is used and is collected in great quantities during the spring shearing. Similarly, the weft is usually of fine wool and is not always dyed. The use of cotton

is entirely incidental. However, there are numerous examples, particularly from the nineteenth Century, of jajim made of silk. Weaving the Jajim

Here, locally produced silk from Azerbaijan and Gilan have been used. The same loom for making jajims is also used to make the tent bands which secure the alachiq, and the bindings around the loads of pack animals. The strips of cloth in a jajim however, are wider and are cut and sewn together to any desired width. Usually, large jajims consist of between three and eight pieces. Innovative return to old carpets in Iran

The technique used to make jajim cloth isa variation on the simplest weaving method: a plain weave of warp and weft. The weft is passed above one warp and under the adjacent warp and

so on, across the width of the cloth. It is then wrapped around the final warp and turned back to repeat the process. If the warp and the weft were evenly spaced out, or rather, if there were

the same number of warp threads in each centimetre of width as the weft in each centimetre of length, the weave would be balanced.

It would be possible to see both the warp and the weft on close inspection. Instead, jajim cloth is ofa special warp- faced type, with the warp threads visible. There are in fact, many more warp threads than wefts. The warps are so dense that they completely cover the fine wefts which link them together, (warp-faced weave).

The Shahsavan call this type of weaving gilica. In essence, it is a similar structure to that of the weft-faced kilim, although in this case the warp is dominant. Consequently, even the simplest decorations can only be arranged vertically.

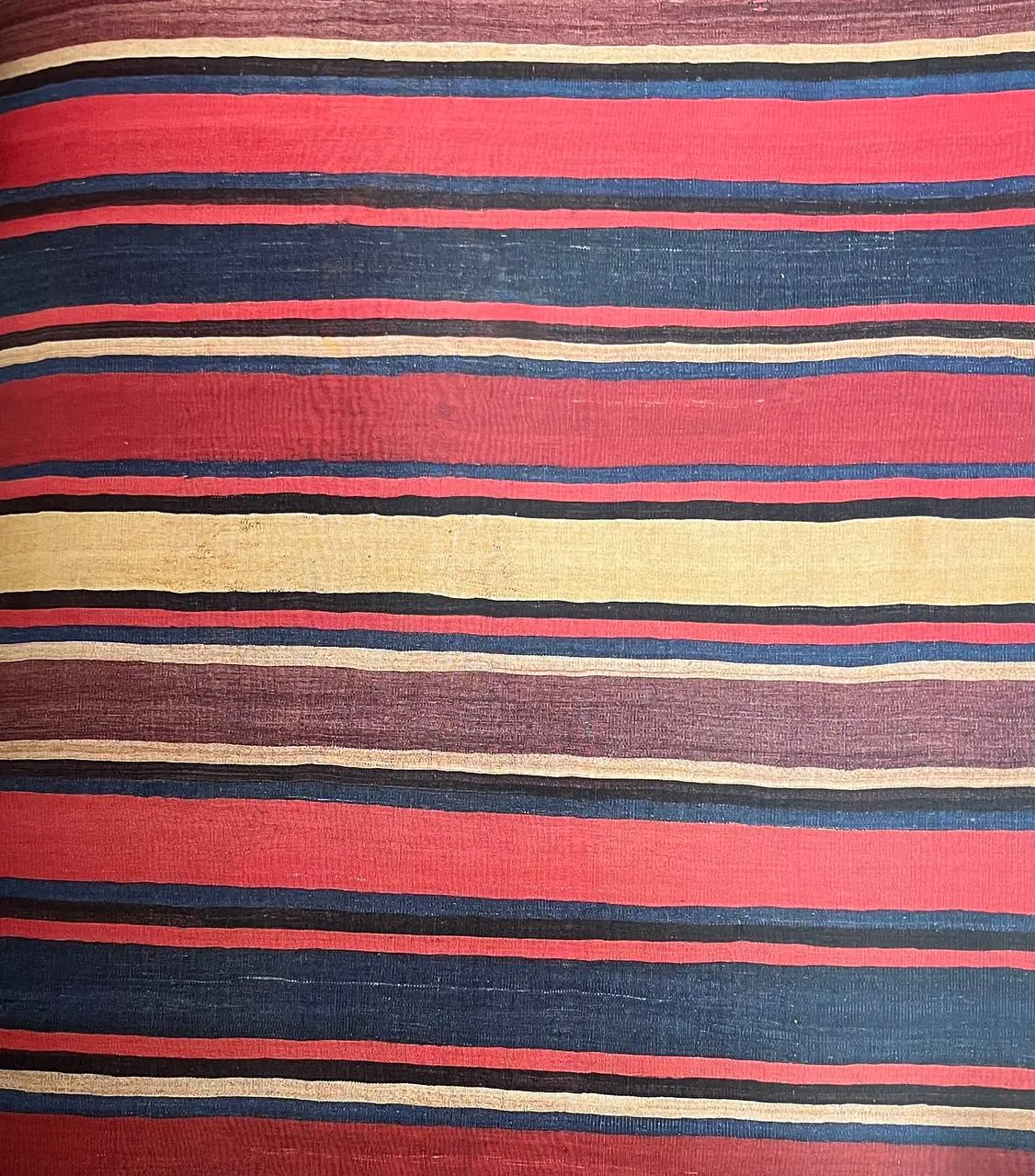

The simplest jajims have no special patterns. The multicoloured stripes are the only decoration and are the result of the simple, tight weave of the wefts and the multicoloured warps.

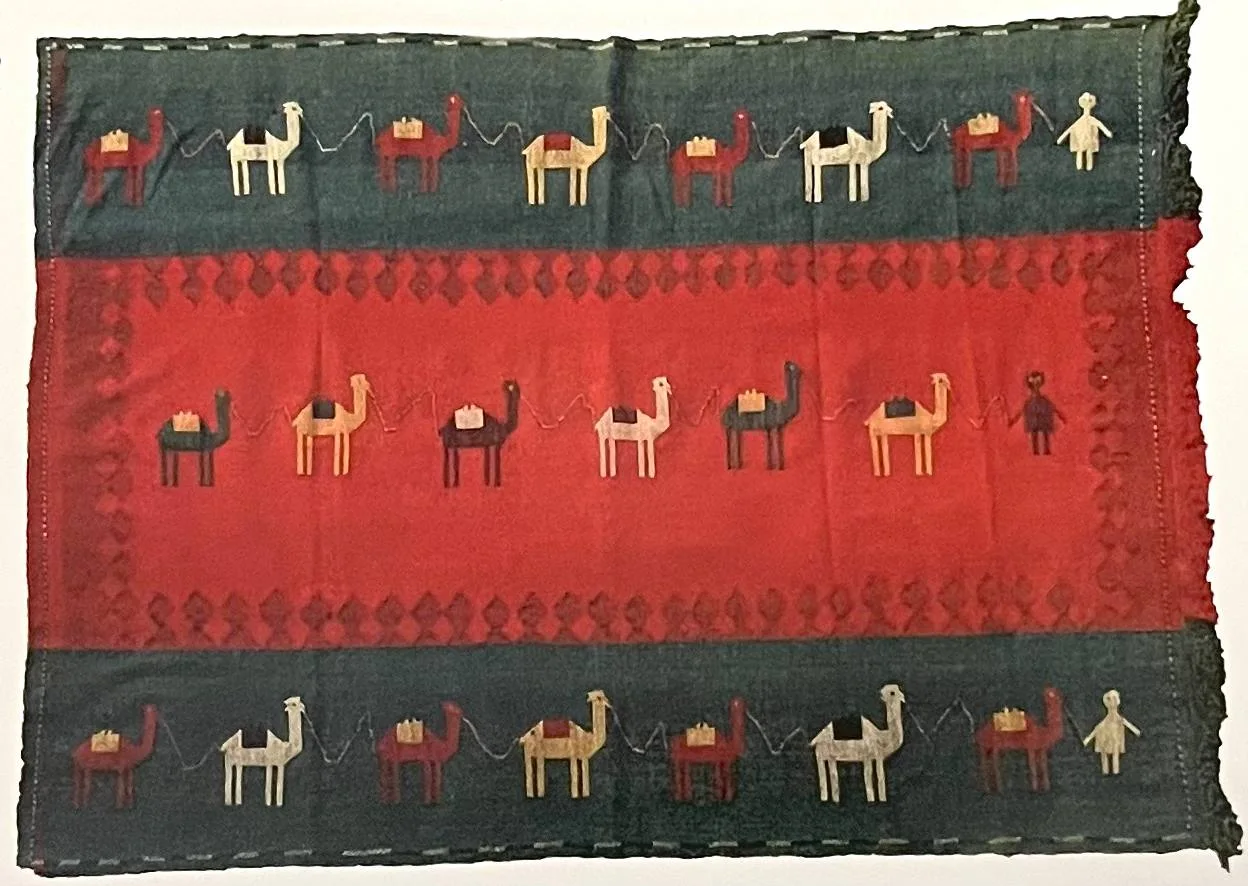

To embellish the cloth, the weavers add a sequence of tiny motifs to each stripe. In order to do this, the weaver must resort to more complicated techniques, known as warp-substitution,

or by its local name ladi, which literally means ‘by brick’. The technique has been adopted mostly by the Shahsavan, who use two different variations.

The first is used only for ordinary cloth and is widely practised. Usually, it consists of decorative warps of contrasting colours which, in line with the design, substitute the warp threads

at the back. These are brought to the front of the design, whereas they usually run freely behind it, (warp-substitution weave).

In most cases, in order to reduce the thickness of the free varn on the back, the weaver uses only one decorative warp. When two or more colours are needed, the cloth inevitably takes on a

certain weight and rigidity. The much more complicated variation is less common among

the Shahsavan. This technique does not make a distinction between back warps and decorative warps. Historical changes styles of Persian carpet

The weaver uses warps of alternate colours, which are brought to the front of the cloth, then to the back alternately. This technique creates a double-faced weave, which is totally reversible, although the colours are reversed, (alternating warp-substitution weave). The decorated vertical bands made with this technique are placed alongside stripes ofjust one colour. These are made by a simple, warp-faced weave with the warp visible. Some decorations are achieved by adding weft threads or rather, by inserting wefts of decorative, multicoloured wool between the structural wefts. Weaving the Jajim

They are then wrapped around the warp threads to form tiny motifs. Jajims made in this way are

much rarer and this technique is known as Chalma or Geçme to the Shahsavan. The finishing techniques are very simple, as one would expect in everyday, household objects. There is no

particular method to protect the selvage, which is made simply by wrapping the structural wefts around the last warp thread.

If necessary, the edges can be strengthened by turning them inwards to form a hem, which is stitched down on the back of the cloth. Sometimes trimmings are added to the hem or a woollen

tape, held in place by a series of cross-stitches.

The ends are not normally given any particular finish, either. Jajims are only very rarely finished off with a fringe. This may be tightly plaited into a flat band, or alternatively, grouped in long,

elaborate plaits. Weaving the Jajim

The fringe is then embellished with tassels Normally, the cloth is finished without any particular treatment and is simply folded over once or twice and hemmed to the back of the cloth. This simplicity is explained by the fact that a jajim is usually woven in one long strip up to 18 or 20

metres in length. This is then cut into several pieces and sewn together to create the desired width. Persian carpet designs

It is quite common to find ribbons at the ends, which serve to reinforce them. These are

often continued around the selvage. They can be added to the sides of the jajim, or placed along the top and sewn down on the reverse side by small stitches.

Sometimes the edges of the jajim are highlighted with a double cord added during the finishing processes, although this 1S not very common. The aim here is to strengthen the ends and

to decorate the work with a coloured frame. The stitching is very careful and not clearly visible.

In theinest pieces, each strip of cloth is placed side by side and sewn with close, cross-stitches placed inside the cloth itself. In other instances, especially when the weaving is coarse, the seams are more obvious: one strip of cloth is placed slightly over the other and a wool cord, sometimes of a contrasting colour, is sewn over the join with a spiral stitch. Weaving the Jajim